Reimagine and Rebuild Mary’s…Naturally!

What is ‘queer’? Being ‘queer’ is not about who you are having sex with, but being ‘queer’ is about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent, create, and find a place to speak, thrive, and live. — Bell Hooks

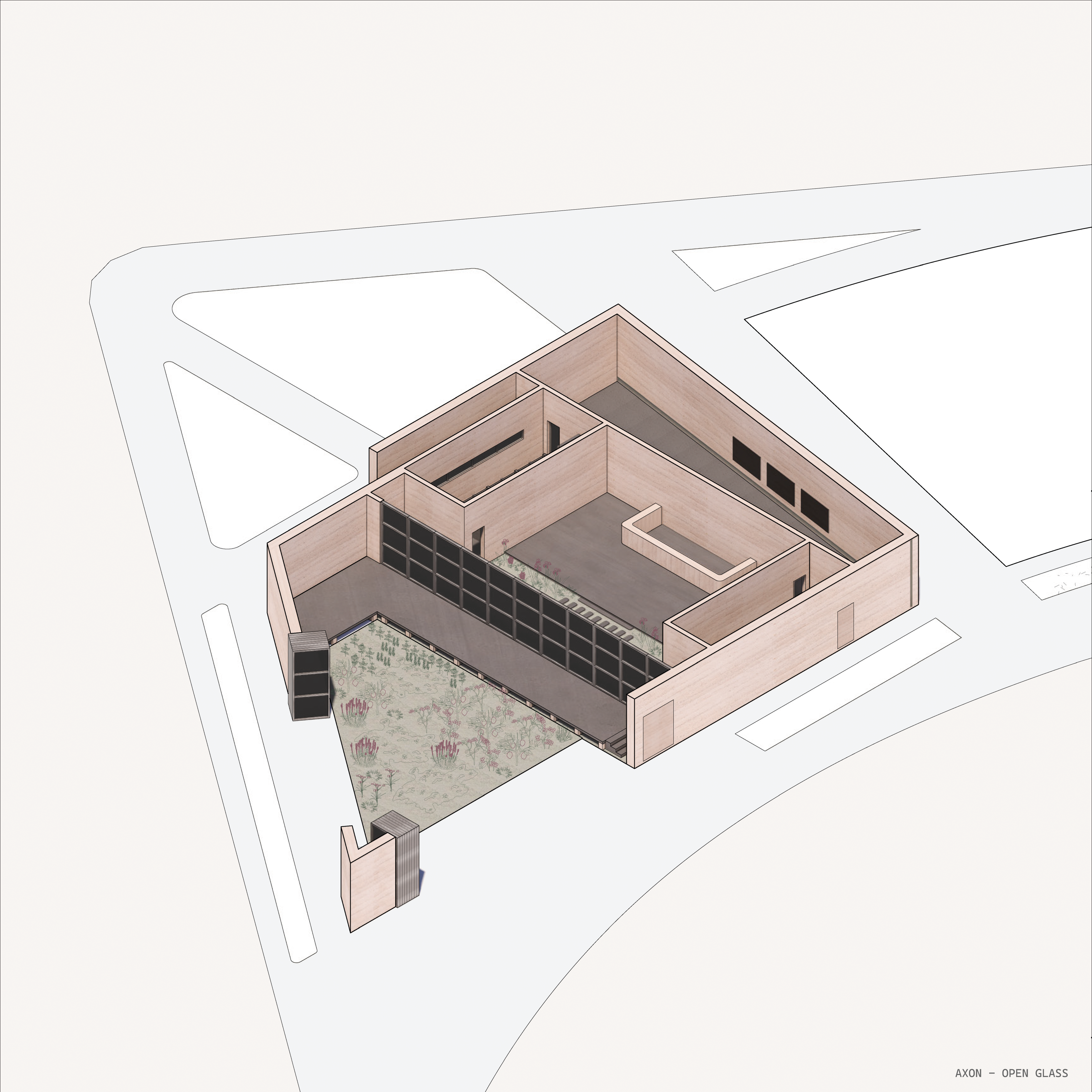

(1) Gallery View. (2) Multi-gender Restroom. (3) Bar View. (4) Outback Courtyard.

Mary’s Story

On the corner of Westheimer and Waugh in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood sits a quaint brick building. What is now known as the Blacksmith cafe was once part of the legendary Houston gay bar Mary’s…Naturally!, from 1970 to 2009. Mary’s, as writer Ed Martinez described it in a spring 1983 issue of Out in Texas, was “the mother house of all the gay bars in Houston”. This gay bar served as the site of many raucous parties, but it also held special social memories for the Houston gay community. During the AIDS era, the bar was where gays would gather to support one another with medical knowledge, and the back patio, called the Outback, was where they would spread the ashes of those who had passed away. The Gulf Coast Archive and Museum of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender History estimates that more than three hundred funeral services were held in Mary’s backyard.

Despite Mary’s significance to Montrose's gayborhood identity at large, the bar was closed down in 2009. The decision to close was influenced by years of poor finances and a shrinking customer base, reflecting shifts in the culture of the gay community. Being gay in Houston is no longer taboo; the presence of Annise Parker, the former Houston mayor and the first lesbian mayor in Houston, celebrated gay identity. The decline of queer-dedicated nightlife spaces is not an isolated occurrence; the Internet has significantly facilitated connections and hookups for people of all sexual orientations, diminishing the necessity of bars for social interaction.

Between these advancements, the gentrification of Montrose, and a growing gay diaspora throughout the city, Mary's was no longer "needed" in the same way it once was. The transformation of Mary’s into Blacksmith and the neglect of the Outback, which held significant social memory for those who endured the AIDS-era, manifests a contested story that contradictory perspectives and different points of interests are held within the space.

During June 2021, a group of Latino artists transformed the Outback site into an exhibition showcasing the exploration of what shifting architecture, gentrification, erasure of history in Montrose means for Houston's queer community today. Titled “without architecture, there would be no stonewall; without architecture, there would be no ‘brick’,” the curators argued that the disappearance of gay bars like Mary’s signal the depoliticization of LGBTQ+ bodies under a neoliberal agenda of “gay rights”. We learned that Houston isn't a city focused on preserving the past but rather on constant new construction every decade for capital gain. When we cease to commemorate the experiences and vital history of marginalized groups, are we inadvertently contributing to their further marginalization and displacement in society?

![]()

On the corner of Westheimer and Waugh in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood sits a quaint brick building. What is now known as the Blacksmith cafe was once part of the legendary Houston gay bar Mary’s…Naturally!, from 1970 to 2009. Mary’s, as writer Ed Martinez described it in a spring 1983 issue of Out in Texas, was “the mother house of all the gay bars in Houston”. This gay bar served as the site of many raucous parties, but it also held special social memories for the Houston gay community. During the AIDS era, the bar was where gays would gather to support one another with medical knowledge, and the back patio, called the Outback, was where they would spread the ashes of those who had passed away. The Gulf Coast Archive and Museum of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender History estimates that more than three hundred funeral services were held in Mary’s backyard.

Despite Mary’s significance to Montrose's gayborhood identity at large, the bar was closed down in 2009. The decision to close was influenced by years of poor finances and a shrinking customer base, reflecting shifts in the culture of the gay community. Being gay in Houston is no longer taboo; the presence of Annise Parker, the former Houston mayor and the first lesbian mayor in Houston, celebrated gay identity. The decline of queer-dedicated nightlife spaces is not an isolated occurrence; the Internet has significantly facilitated connections and hookups for people of all sexual orientations, diminishing the necessity of bars for social interaction.

Between these advancements, the gentrification of Montrose, and a growing gay diaspora throughout the city, Mary's was no longer "needed" in the same way it once was. The transformation of Mary’s into Blacksmith and the neglect of the Outback, which held significant social memory for those who endured the AIDS-era, manifests a contested story that contradictory perspectives and different points of interests are held within the space.

During June 2021, a group of Latino artists transformed the Outback site into an exhibition showcasing the exploration of what shifting architecture, gentrification, erasure of history in Montrose means for Houston's queer community today. Titled “without architecture, there would be no stonewall; without architecture, there would be no ‘brick’,” the curators argued that the disappearance of gay bars like Mary’s signal the depoliticization of LGBTQ+ bodies under a neoliberal agenda of “gay rights”. We learned that Houston isn't a city focused on preserving the past but rather on constant new construction every decade for capital gain. When we cease to commemorate the experiences and vital history of marginalized groups, are we inadvertently contributing to their further marginalization and displacement in society?

Cultural landscapes serve as arenas for social action in the present and as foundations for community aspirations for the future. Philosopher Edward S. Casey defines “place memory” as the enduring persistence of a place that contains experiences contributing powerfully to human memorability. Places evoke memories for insiders who share a common past, while simultaneously serving as representations of shared histories for outsiders interested in learning about them in the present. When we design for a narrative of an inclusive and equitable future with critical reflection and reimagination of the past, communities can utilize places to reclaim history, retrieve memory, and shape identities.

Materiality

The materiality of place is crucial for the establishment of place memory, which empowers, resists, and unites people. In Mary's case, the materiality that constructs the place memory is embedded in its various architectural features. It is the brick wall, which is tied back to the first brick thrown at the Stonewall Riot and symbolizes the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement in its built form. It is the bar top adorned with photographs of lovers and fighters who supported each other during the AIDS epidemic. It is the Outback, where unconventional acts of mourning in our current society are embraced and celebrated—ashes are scattered and buried, and greenery is planted over the marker. It is also the murals by Scott Swoveland, whose images celebrate the expression of queer bodies but also highlight Annise Parker's point that, at the time, it was predominantly a white-male-centered gay culture.

In this design project, I propose rammed earth as a new materiality that references brick while providing the same sense of elegance, permanence, and durability. By mixing Houston’s local dirt, part of it could be taken from Mary’s Outback with people’s ashes, with water and Portland cement, rammed earth provides a sustainable, locally sourced, and locally constructed architectural solution. I also reuse blackout glasses as a classical feature that references gay bar characteristics. When approached from the street, you can immediately grasp the vibe of a gay bar.

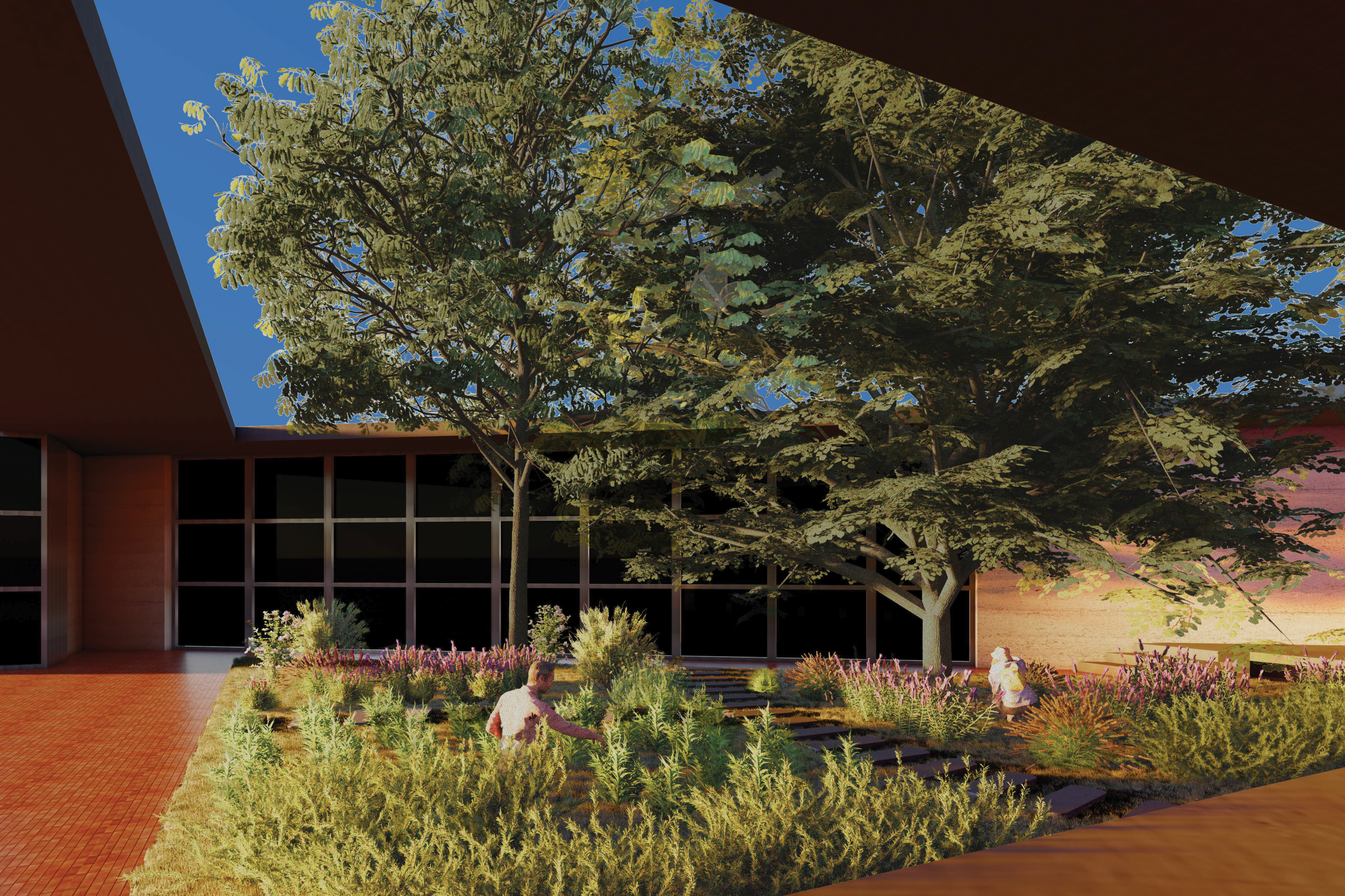

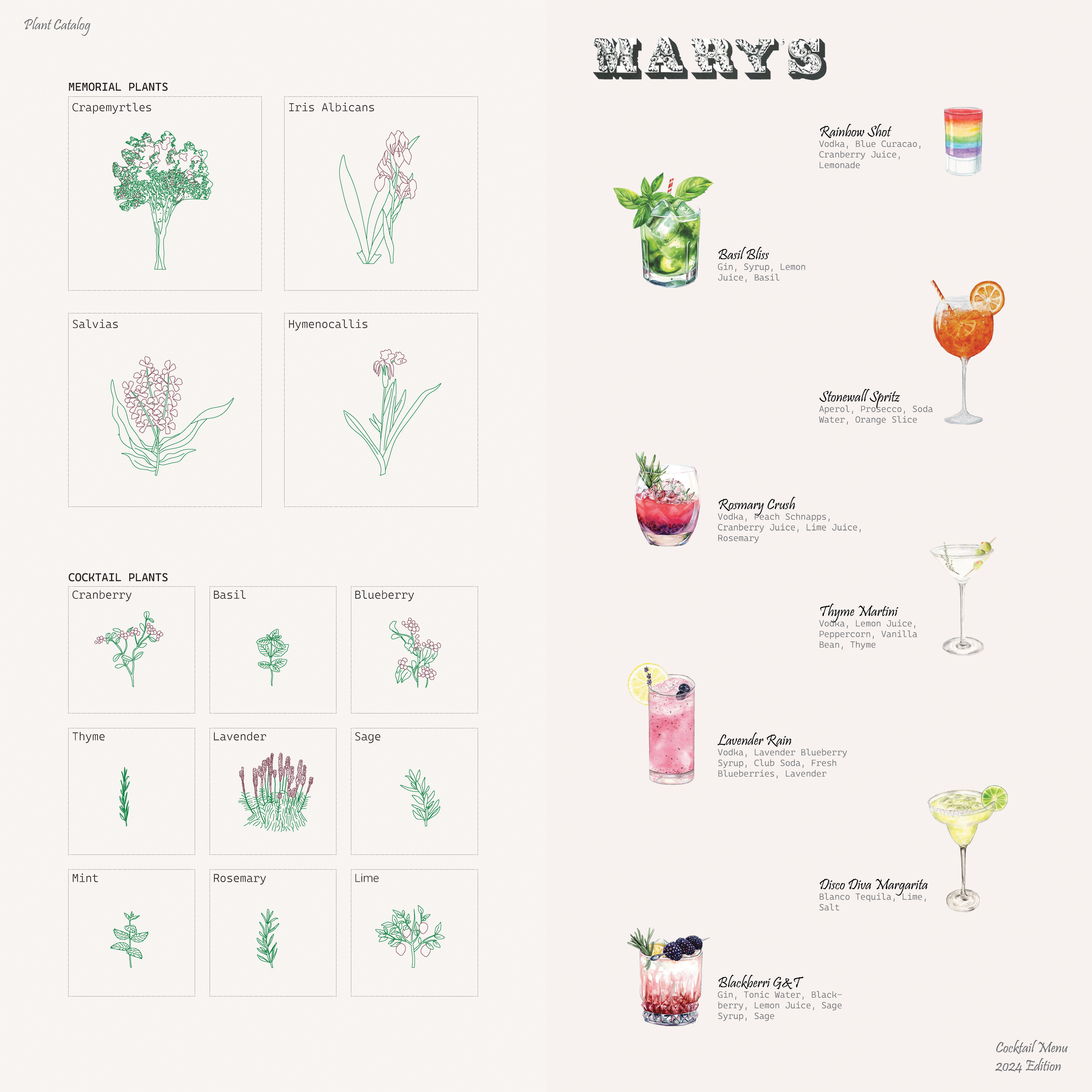

Memorial Garden

Central to the design is the Outback, which functions as both a memorial garden and a herbal garden that serves the bar. Memorial plants, such as crapemyrtles, Iris Albicans, Salvias, and Hymenocallis, create a vibrant garden that pays homage to those who passed away during the AIDS epidemic. Additionally, fruits and herbs such as cranberry, blueberry, thyme, lavender, sage, mint, rosemary, and lime can be picked for cocktail drinks served to the clientele. A cocktail menu is created specifically for this garden. Many of them reference the significance of the LGBTQ+ history and identity, such as Rainbow Shot, Stonewall Spritz, and Lavender Rain. Others use herbs and fruits from the garden, such as Basil Bliss, Rosemary Crush, Thyme Martini, and Blackberri G&T.

![]()

Materiality

The materiality of place is crucial for the establishment of place memory, which empowers, resists, and unites people. In Mary's case, the materiality that constructs the place memory is embedded in its various architectural features. It is the brick wall, which is tied back to the first brick thrown at the Stonewall Riot and symbolizes the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement in its built form. It is the bar top adorned with photographs of lovers and fighters who supported each other during the AIDS epidemic. It is the Outback, where unconventional acts of mourning in our current society are embraced and celebrated—ashes are scattered and buried, and greenery is planted over the marker. It is also the murals by Scott Swoveland, whose images celebrate the expression of queer bodies but also highlight Annise Parker's point that, at the time, it was predominantly a white-male-centered gay culture.

In this design project, I propose rammed earth as a new materiality that references brick while providing the same sense of elegance, permanence, and durability. By mixing Houston’s local dirt, part of it could be taken from Mary’s Outback with people’s ashes, with water and Portland cement, rammed earth provides a sustainable, locally sourced, and locally constructed architectural solution. I also reuse blackout glasses as a classical feature that references gay bar characteristics. When approached from the street, you can immediately grasp the vibe of a gay bar.

Memorial Garden

Central to the design is the Outback, which functions as both a memorial garden and a herbal garden that serves the bar. Memorial plants, such as crapemyrtles, Iris Albicans, Salvias, and Hymenocallis, create a vibrant garden that pays homage to those who passed away during the AIDS epidemic. Additionally, fruits and herbs such as cranberry, blueberry, thyme, lavender, sage, mint, rosemary, and lime can be picked for cocktail drinks served to the clientele. A cocktail menu is created specifically for this garden. Many of them reference the significance of the LGBTQ+ history and identity, such as Rainbow Shot, Stonewall Spritz, and Lavender Rain. Others use herbs and fruits from the garden, such as Basil Bliss, Rosemary Crush, Thyme Martini, and Blackberri G&T.

Preserve place memory through design

As designers, we possess the ability to utilize tangible materials to spatialize social memories and preserve intangible heritage and community values. When objects and the materiality of space are imbued with social memory and shared narratives, they transcend their functional meanings as mere objects and spaces, becoming agents that transform historical consciousness into future motives (Lydon, 655). By reimagining and reconstructing the materiality of elements such as brick walls, countertops, backyards, and murals in a sustainable and renewable manner, we can recreate a conception of identity that not only recaptures place memory but also looks forward, suggesting inclusiveness among different social groups.

It is crucial to recognize the coexistence of cultural values that are contested between universal values that serve dominant interests and the personal narratives of marginalized groups. Understanding and reconciling these diverse interests can be challenging. However, it is important to acknowledge and continue engaging with these contested spaces. The existence of gay bars serves more than just a physical representation of self-identifications; such spaces also serve as sites of contestation and questioning of the potential oppression faced by specific identity minorities in "normal" society. They are visited, claimed, and transformed through the presence of queer bodies. By reimagining and rebuilding Mary’s, we can transform generational trauma into resilience and empower queerness—not only within the gay community but across numerous marginalized communities defined by race, age, ability, nationality, and economic status—to combat injustice and forge an inclusive future together.

![]()

![]()

As designers, we possess the ability to utilize tangible materials to spatialize social memories and preserve intangible heritage and community values. When objects and the materiality of space are imbued with social memory and shared narratives, they transcend their functional meanings as mere objects and spaces, becoming agents that transform historical consciousness into future motives (Lydon, 655). By reimagining and reconstructing the materiality of elements such as brick walls, countertops, backyards, and murals in a sustainable and renewable manner, we can recreate a conception of identity that not only recaptures place memory but also looks forward, suggesting inclusiveness among different social groups.

It is crucial to recognize the coexistence of cultural values that are contested between universal values that serve dominant interests and the personal narratives of marginalized groups. Understanding and reconciling these diverse interests can be challenging. However, it is important to acknowledge and continue engaging with these contested spaces. The existence of gay bars serves more than just a physical representation of self-identifications; such spaces also serve as sites of contestation and questioning of the potential oppression faced by specific identity minorities in "normal" society. They are visited, claimed, and transformed through the presence of queer bodies. By reimagining and rebuilding Mary’s, we can transform generational trauma into resilience and empower queerness—not only within the gay community but across numerous marginalized communities defined by race, age, ability, nationality, and economic status—to combat injustice and forge an inclusive future together.