Reimagine and Rebuild Mary’s…Naturally!

What is ‘queer’? Being ‘queer’ is not about who you are having sex with, but being ‘queer’ is about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent, create, and find a place to speak, thrive, and live. — Bell Hooks

(1) Gallery View. (2) Multi-gender Restroom. (3) Bar View. (4) Outback Courtyard.

Mary’s Story

On the corner of Westheimer and Waugh in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood sits a quaint brick building. What is now known as the Blacksmith cafe was once part of the legendary Houston gay bar Mary’s…Naturally!, from 1970 to 2009. Mary’s, as writer Ed Martinez described it in a spring 1983 issue of Out in Texas, was “the mother house of all the gay bars in Houston”. This gay bar served as the site of many raucous parties, but it also held special social memories for the Houston gay community. During the AIDS era, the bar was where gays would gather to support one another with medical knowledge, and the back patio, called the Outback, was where they would spread the ashes of those who had passed away. The Gulf Coast Archive and Museum of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender History estimates that more than three hundred funeral services were held in Mary’s backyard.

Despite Mary’s significance to Montrose's gayborhood identity at large, the bar was closed down in 2009. The decision to close was influenced by years of poor finances and a shrinking customer base, reflecting shifts in the culture of the gay community. Being gay in Houston is no longer taboo; the presence of Annise Parker, the former Houston mayor and the first lesbian mayor in Houston, celebrated gay identity. The decline of queer-dedicated nightlife spaces is not an isolated occurrence; the Internet has significantly facilitated connections and hookups for people of all sexual orientations, diminishing the necessity of bars for social interaction.

Between these advancements, the gentrification of Montrose, and a growing gay diaspora throughout the city, Mary's was no longer "needed" in the same way it once was. The transformation of Mary’s into Blacksmith and the neglect of the Outback, which held significant social memory for those who endured the AIDS-era, manifests a contested story that contradictory perspectives and different points of interests are held within the space.

During June 2021, a group of Latino artists transformed the Outback site into an exhibition showcasing the exploration of what shifting architecture, gentrification, erasure of history in Montrose means for Houston's queer community today. Titled “without architecture, there would be no stonewall; without architecture, there would be no ‘brick’,” the curators argued that the disappearance of gay bars like Mary’s signal the depoliticization of LGBTQ+ bodies under a neoliberal agenda of “gay rights”. We learned that Houston isn't a city focused on preserving the past but rather on constant new construction every decade for capital gain. When we cease to commemorate the experiences and vital history of marginalized groups, are we inadvertently contributing to their further marginalization and displacement in society?

![]()

On the corner of Westheimer and Waugh in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood sits a quaint brick building. What is now known as the Blacksmith cafe was once part of the legendary Houston gay bar Mary’s…Naturally!, from 1970 to 2009. Mary’s, as writer Ed Martinez described it in a spring 1983 issue of Out in Texas, was “the mother house of all the gay bars in Houston”. This gay bar served as the site of many raucous parties, but it also held special social memories for the Houston gay community. During the AIDS era, the bar was where gays would gather to support one another with medical knowledge, and the back patio, called the Outback, was where they would spread the ashes of those who had passed away. The Gulf Coast Archive and Museum of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender History estimates that more than three hundred funeral services were held in Mary’s backyard.

Despite Mary’s significance to Montrose's gayborhood identity at large, the bar was closed down in 2009. The decision to close was influenced by years of poor finances and a shrinking customer base, reflecting shifts in the culture of the gay community. Being gay in Houston is no longer taboo; the presence of Annise Parker, the former Houston mayor and the first lesbian mayor in Houston, celebrated gay identity. The decline of queer-dedicated nightlife spaces is not an isolated occurrence; the Internet has significantly facilitated connections and hookups for people of all sexual orientations, diminishing the necessity of bars for social interaction.

Between these advancements, the gentrification of Montrose, and a growing gay diaspora throughout the city, Mary's was no longer "needed" in the same way it once was. The transformation of Mary’s into Blacksmith and the neglect of the Outback, which held significant social memory for those who endured the AIDS-era, manifests a contested story that contradictory perspectives and different points of interests are held within the space.

During June 2021, a group of Latino artists transformed the Outback site into an exhibition showcasing the exploration of what shifting architecture, gentrification, erasure of history in Montrose means for Houston's queer community today. Titled “without architecture, there would be no stonewall; without architecture, there would be no ‘brick’,” the curators argued that the disappearance of gay bars like Mary’s signal the depoliticization of LGBTQ+ bodies under a neoliberal agenda of “gay rights”. We learned that Houston isn't a city focused on preserving the past but rather on constant new construction every decade for capital gain. When we cease to commemorate the experiences and vital history of marginalized groups, are we inadvertently contributing to their further marginalization and displacement in society?

Cultural landscapes serve as arenas for social action in the present and as foundations for community aspirations for the future. Philosopher Edward S. Casey defines “place memory” as the enduring persistence of a place that contains experiences contributing powerfully to human memorability. Places evoke memories for insiders who share a common past, while simultaneously serving as representations of shared histories for outsiders interested in learning about them in the present. When we design for a narrative of an inclusive and equitable future with critical reflection and reimagination of the past, communities can utilize places to reclaim history, retrieve memory, and shape identities.

Materiality

The materiality of place is crucial for the establishment of place memory, which empowers, resists, and unites people. In Mary's case, the materiality that constructs the place memory is embedded in its various architectural features. It is the brick wall, which is tied back to the first brick thrown at the Stonewall Riot and symbolizes the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement in its built form. It is the bar top adorned with photographs of lovers and fighters who supported each other during the AIDS epidemic. It is the Outback, where unconventional acts of mourning in our current society are embraced and celebrated—ashes are scattered and buried, and greenery is planted over the marker. It is also the murals by Scott Swoveland, whose images celebrate the expression of queer bodies but also highlight Annise Parker's point that, at the time, it was predominantly a white-male-centered gay culture.

In this design project, I propose rammed earth as a new materiality that references brick while providing the same sense of elegance, permanence, and durability. By mixing Houston’s local dirt, part of it could be taken from Mary’s Outback with people’s ashes, with water and Portland cement, rammed earth provides a sustainable, locally sourced, and locally constructed architectural solution. I also reuse blackout glasses as a classical feature that references gay bar characteristics. When approached from the street, you can immediately grasp the vibe of a gay bar.

Memorial Garden

Central to the design is the Outback, which functions as both a memorial garden and a herbal garden that serves the bar. Memorial plants, such as crapemyrtles, Iris Albicans, Salvias, and Hymenocallis, create a vibrant garden that pays homage to those who passed away during the AIDS epidemic. Additionally, fruits and herbs such as cranberry, blueberry, thyme, lavender, sage, mint, rosemary, and lime can be picked for cocktail drinks served to the clientele. A cocktail menu is created specifically for this garden. Many of them reference the significance of the LGBTQ+ history and identity, such as Rainbow Shot, Stonewall Spritz, and Lavender Rain. Others use herbs and fruits from the garden, such as Basil Bliss, Rosemary Crush, Thyme Martini, and Blackberri G&T.

![]()

Materiality

The materiality of place is crucial for the establishment of place memory, which empowers, resists, and unites people. In Mary's case, the materiality that constructs the place memory is embedded in its various architectural features. It is the brick wall, which is tied back to the first brick thrown at the Stonewall Riot and symbolizes the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement in its built form. It is the bar top adorned with photographs of lovers and fighters who supported each other during the AIDS epidemic. It is the Outback, where unconventional acts of mourning in our current society are embraced and celebrated—ashes are scattered and buried, and greenery is planted over the marker. It is also the murals by Scott Swoveland, whose images celebrate the expression of queer bodies but also highlight Annise Parker's point that, at the time, it was predominantly a white-male-centered gay culture.

In this design project, I propose rammed earth as a new materiality that references brick while providing the same sense of elegance, permanence, and durability. By mixing Houston’s local dirt, part of it could be taken from Mary’s Outback with people’s ashes, with water and Portland cement, rammed earth provides a sustainable, locally sourced, and locally constructed architectural solution. I also reuse blackout glasses as a classical feature that references gay bar characteristics. When approached from the street, you can immediately grasp the vibe of a gay bar.

Memorial Garden

Central to the design is the Outback, which functions as both a memorial garden and a herbal garden that serves the bar. Memorial plants, such as crapemyrtles, Iris Albicans, Salvias, and Hymenocallis, create a vibrant garden that pays homage to those who passed away during the AIDS epidemic. Additionally, fruits and herbs such as cranberry, blueberry, thyme, lavender, sage, mint, rosemary, and lime can be picked for cocktail drinks served to the clientele. A cocktail menu is created specifically for this garden. Many of them reference the significance of the LGBTQ+ history and identity, such as Rainbow Shot, Stonewall Spritz, and Lavender Rain. Others use herbs and fruits from the garden, such as Basil Bliss, Rosemary Crush, Thyme Martini, and Blackberri G&T.

Preserve place memory through design

As designers, we possess the ability to utilize tangible materials to spatialize social memories and preserve intangible heritage and community values. When objects and the materiality of space are imbued with social memory and shared narratives, they transcend their functional meanings as mere objects and spaces, becoming agents that transform historical consciousness into future motives (Lydon, 655). By reimagining and reconstructing the materiality of elements such as brick walls, countertops, backyards, and murals in a sustainable and renewable manner, we can recreate a conception of identity that not only recaptures place memory but also looks forward, suggesting inclusiveness among different social groups.

It is crucial to recognize the coexistence of cultural values that are contested between universal values that serve dominant interests and the personal narratives of marginalized groups. Understanding and reconciling these diverse interests can be challenging. However, it is important to acknowledge and continue engaging with these contested spaces. The existence of gay bars serves more than just a physical representation of self-identifications; such spaces also serve as sites of contestation and questioning of the potential oppression faced by specific identity minorities in "normal" society. They are visited, claimed, and transformed through the presence of queer bodies. By reimagining and rebuilding Mary’s, we can transform generational trauma into resilience and empower queerness—not only within the gay community but across numerous marginalized communities defined by race, age, ability, nationality, and economic status—to combat injustice and forge an inclusive future together.

![]()

![]()

As designers, we possess the ability to utilize tangible materials to spatialize social memories and preserve intangible heritage and community values. When objects and the materiality of space are imbued with social memory and shared narratives, they transcend their functional meanings as mere objects and spaces, becoming agents that transform historical consciousness into future motives (Lydon, 655). By reimagining and reconstructing the materiality of elements such as brick walls, countertops, backyards, and murals in a sustainable and renewable manner, we can recreate a conception of identity that not only recaptures place memory but also looks forward, suggesting inclusiveness among different social groups.

It is crucial to recognize the coexistence of cultural values that are contested between universal values that serve dominant interests and the personal narratives of marginalized groups. Understanding and reconciling these diverse interests can be challenging. However, it is important to acknowledge and continue engaging with these contested spaces. The existence of gay bars serves more than just a physical representation of self-identifications; such spaces also serve as sites of contestation and questioning of the potential oppression faced by specific identity minorities in "normal" society. They are visited, claimed, and transformed through the presence of queer bodies. By reimagining and rebuilding Mary’s, we can transform generational trauma into resilience and empower queerness—not only within the gay community but across numerous marginalized communities defined by race, age, ability, nationality, and economic status—to combat injustice and forge an inclusive future together.

Passage Couvert

Located in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, bounded by the railway tracks bundle of Gare de Lyon, Passage Couvert envisions an adaptive reuse of the existing reinforced concrete building into a hybrid of care spaces for the community. Reflecting upon the historical significance of traditional trades and crafts in the district and the psychological benefits of art-making, the programs amalgamate individual and group art therapy with community craft-making workshops, commercial craft shops, and housing for craftsmen.

Rooted in the vibrant urban context of Paris, the existing typology of both covered and open-air walkways serves as a design parti for our architectural intervention. The poetry of Gallerie Vivienne—the glass roof and window adorned with musical instruments, children’s toys, and the smell of food—drives our desire to incorporate the Parisian experience into the heart of our project. Imagine a space where a ceramic shop sits next to a woodworking fabrication lab, a restored medieval painting coexists with a modern stool; this covered passage becomes a vibrant tapestry where craftsmen, travelers, and therapy seekers mingle under a shared roof, transcending time and traditions.

This project introduces timber as a new material, advocating for sustainable construction and a healing and supportive environment. The warm and natural aesthetic of timber creates a calming and inviting atmosphere, offering comfortable conditions for housing and intimate therapy spaces. As a renewable resource, timber has a low environmental impact and can maintain thermal comfort while absorbing sound. This material interacts with the existing concrete structure, fostering a generative energy that flows between the old and the new.

Left images: (1) Courtyard Housing for Craftsmen. (2) Covered Passage. (3) Community Craft Workshop. (4) Group Art Therapy. (5) Gallerie for Retail & Cafe. (6) Private Therapy / Health Clinic.

Fall 2023, collab with Andrea Sanchez.

Located in the 12th arrondissement of Paris, bounded by the railway tracks bundle of Gare de Lyon, Passage Couvert envisions an adaptive reuse of the existing reinforced concrete building into a hybrid of care spaces for the community. Reflecting upon the historical significance of traditional trades and crafts in the district and the psychological benefits of art-making, the programs amalgamate individual and group art therapy with community craft-making workshops, commercial craft shops, and housing for craftsmen.

Rooted in the vibrant urban context of Paris, the existing typology of both covered and open-air walkways serves as a design parti for our architectural intervention. The poetry of Gallerie Vivienne—the glass roof and window adorned with musical instruments, children’s toys, and the smell of food—drives our desire to incorporate the Parisian experience into the heart of our project. Imagine a space where a ceramic shop sits next to a woodworking fabrication lab, a restored medieval painting coexists with a modern stool; this covered passage becomes a vibrant tapestry where craftsmen, travelers, and therapy seekers mingle under a shared roof, transcending time and traditions.

This project introduces timber as a new material, advocating for sustainable construction and a healing and supportive environment. The warm and natural aesthetic of timber creates a calming and inviting atmosphere, offering comfortable conditions for housing and intimate therapy spaces. As a renewable resource, timber has a low environmental impact and can maintain thermal comfort while absorbing sound. This material interacts with the existing concrete structure, fostering a generative energy that flows between the old and the new.

Left images: (1) Courtyard Housing for Craftsmen. (2) Covered Passage. (3) Community Craft Workshop. (4) Group Art Therapy. (5) Gallerie for Retail & Cafe. (6) Private Therapy / Health Clinic.

Fall 2023, collab with Andrea Sanchez.

Urban Typology Research: Plan & Section

Urban Typology Research: Plan & SectionThe open-air quality of Passage du Cheval Blanc (upper left) inspires the new timber massing, creating a condition where residential units sit above ground-floor commercial craft stores. Passersby enter beneath a building facade that seamlessly aligns with the street, only to find themselves in an open-air courtyard for repose and social interaction.

Galerie Vivienne (upper right) is a renowned Parisian covered passage adorned with glass roofs. By mirroring the existing architectural language of the concrete archway, our passage constructed in wood and glass serves as the central circulation that links the existing and new structures.

Site Noli Plan

Sections

Program Diagram, Adaptive Reuse Axonometric

Program Diagram, Adaptive Reuse Axonometric

Material Assembly Detail

Fabric Care

Fabric Care reimagines Christo and Jeanne Claude’s Running Fence as a sand capturing system that will repair the damaged sand dunes in West Texas. Due to expanding sand mining and oil fracking activities, the oil and sand field of Permian Basin will estimate to be depleted in a hundred years. Lasting for three stages from 2050 to post 2100, this project proposes a landscape and an adaptive reuse strategy that turns current mining facilities into a testing lab, housing for terrestrial care workers, and a future public educational and recreational site.

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, is a drilling technology used for extracting oil, natural gas, geothermal energy, or water from deep underground. Silica sand is used to keep fissures open and facilitate oil or natural gas flow from fissures into well. Permian basin is the largest petroleum-producing basin in the United States. Kermit Sand Hill sits on the central carbonate platform between the Delaware Basin and Midland Basin, where oil and natural gas are produced. The sand hill is formed through the accumulation of sand blowing from the nearby Pecos River. The supply of silica sand in central carbonate platform facilitates the oil fracking industry to extract more oil from the ground.

The installation of the running fence engages with local work forces, turning a technical geoengineering construction into a creative, caring, and almost ritualistic practice. The silos of current sand quarries will be kept as a historic monument, to remind and educate future generations the damage humans have done to the landscape. After the rehabilitation is completed, the Kermit Sand Hill will be reopened to the public, presenting the restored landscape and the intertwined history between humans and nature.

Left images: (1) Post-quarry Stage (2020-2050): deconstruction & adaptation of sand mining facilities; installation of running fabric. (2) Rehabilitation Stage (2050-2070): geological and environmental research; housing for terrestrial care workers, researchers, and nature lovers; sand dune rehabilitation, preservation of ecology. (3) Future Land Use (2070-): educational and recreational landscape for public access.

Spring 2022, independent work.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Fabric Care reimagines Christo and Jeanne Claude’s Running Fence as a sand capturing system that will repair the damaged sand dunes in West Texas. Due to expanding sand mining and oil fracking activities, the oil and sand field of Permian Basin will estimate to be depleted in a hundred years. Lasting for three stages from 2050 to post 2100, this project proposes a landscape and an adaptive reuse strategy that turns current mining facilities into a testing lab, housing for terrestrial care workers, and a future public educational and recreational site.

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking”, is a drilling technology used for extracting oil, natural gas, geothermal energy, or water from deep underground. Silica sand is used to keep fissures open and facilitate oil or natural gas flow from fissures into well. Permian basin is the largest petroleum-producing basin in the United States. Kermit Sand Hill sits on the central carbonate platform between the Delaware Basin and Midland Basin, where oil and natural gas are produced. The sand hill is formed through the accumulation of sand blowing from the nearby Pecos River. The supply of silica sand in central carbonate platform facilitates the oil fracking industry to extract more oil from the ground.

The installation of the running fence engages with local work forces, turning a technical geoengineering construction into a creative, caring, and almost ritualistic practice. The silos of current sand quarries will be kept as a historic monument, to remind and educate future generations the damage humans have done to the landscape. After the rehabilitation is completed, the Kermit Sand Hill will be reopened to the public, presenting the restored landscape and the intertwined history between humans and nature.

Left images: (1) Post-quarry Stage (2020-2050): deconstruction & adaptation of sand mining facilities; installation of running fabric. (2) Rehabilitation Stage (2050-2070): geological and environmental research; housing for terrestrial care workers, researchers, and nature lovers; sand dune rehabilitation, preservation of ecology. (3) Future Land Use (2070-): educational and recreational landscape for public access.

Spring 2022, independent work.

Erased Body, Measured Earth

Guggenheim Summer College Workshop is a remote enrichment program open to current undergraduate and graduate students from any major or discipline. Unlike the Guggenheim’s internship program, the Workshop is an experimental classroom for students to collaborate and design their own project inspired by an exhibition at the museum. Volume III: Reimagining and Reinventing Rituals (2022) is a visual archive of 16 projects that examine how people use rituals to celebrate, commemorate, and define the human experience. The Workshop theme was inspired by the exhibition Cecilia Vicuña: Spin Spin Triangulene. My project Erased Body, Measured Earth reflected on the ritual of Long Kowtow through a painting and interview.

You can read our collective e-book here: https://readymag.com/u1881633060/3914102/

The Long Kowtow is a ritual in Tibetan Buddhism. Kowtow, the act of kneeling and touching the ground with the forehead, originated in Chinese Han culture and was adapted by Tibetan Buddhism to express religious reverence. Long Kowtow is the performance of kowows from one place, usually the Buddhists’ hometown, to Lhasa, the Holy City of Tibet. Palms put together, Buddhists prostrate themselves with the head, arms, and knees on the ground; from this position, they move forward slowly, after every step returning to a kowtow. While doing the kowtow, they chant the six-syllable Sanskrit mantra—Om mani padme hum—without stopping. Once in their lifetime, many Tibetan Buddhists choose to embark on a pilgrimage. Traveling the earthly distance with their head kowtowed, Buddhists make intimate connections with the vast landscape and devote their mind and body to Buddhist practice.

I interviewed a Tibetan Buddhist, Suomucheng, who took a pilgrimage from his hometown in Qinghai province in China to Lhasa. The interview provides a comprehensive look into Suomucheng and his journey, describing his background and the significance of his pilgrimage as well as its details, from what he wore and ate to the time he rose and slept. Suo speaks both about the challenges and impressions of his experience and how it changed his view of nature. The interview was conducted and translated through the help of Suomucheng’s nephew Dr. Teyun, who received a doctoral degree from Qinghai Tibetan Buddhism College and holds important positions in Longshijia Temple.

Alongside the interview, I created a painting (18 x 24 inches) that depicts the steps of Long Kowtow performed by the Buddhist. Red marks the monk cassocks typically worn by Buddhists. It also symbolizes the pilgrim’s spirit and the holy light in Suomucheng’s dream, which inspired him to embark on his journey. In the background, the textured snow mountain is Nyenpo Yurtse Snow Mountain, Suomucheng’s home and where his first pilgrimage began. As Suo said, “Nature is both the biggest obstacle and the most intimate company to pilgrims.” While the transient body movement in the painting contrasts with the heaviness of mountains, the figures also blend into the landscape, as if wanting to become part of it.

I first encountered the ritual of kowtow when I was fifteen, traveling in Qinghai with my parents in midsummer. Among the bustling crowd and unceasing noises of Ta’er Temple, one figure caught my eyes. Dressed in a red cassock, he stood alone in the corridor in front of the temple. Suddenly his whole body fell to the ground. His hands stretched from his chest over to his head, with rags in his hands wiping the ground from back to front. He stood up, and fell again, moving forward with the same action, slowly yet tirelessly. His movement was so powerful that I could almost hear the wind blowing with his body. The ground beneath him was wiped so hard and so many times that it shined brightly. “He is a Buddhist who lives in the monastery and practices kowtow every morning till dawn,” the tour guide told us. “There are many like him here.” Many tourists stopped to watch this scene, yet the Buddhist performed meticulously as if no one was around him. Sweat glistened on his forehead like crystalized beads. At that moment, I felt like I was stepping into a force so tenacious and unbreakable that nothing in this world could stop the Buddhist from performing his ritual. Around him time seemed to fade away. All the trifling disturbances of life were reduced and erased by the repetition of one simple body movement.

I interviewed a Tibetan Buddhist, Suomucheng, who took a pilgrimage from his hometown in Qinghai province in China to Lhasa. The interview provides a comprehensive look into Suomucheng and his journey, describing his background and the significance of his pilgrimage as well as its details, from what he wore and ate to the time he rose and slept. Suo speaks both about the challenges and impressions of his experience and how it changed his view of nature. The interview was conducted and translated through the help of Suomucheng’s nephew Dr. Teyun, who received a doctoral degree from Qinghai Tibetan Buddhism College and holds important positions in Longshijia Temple.

Alongside the interview, I created a painting (18 x 24 inches) that depicts the steps of Long Kowtow performed by the Buddhist. Red marks the monk cassocks typically worn by Buddhists. It also symbolizes the pilgrim’s spirit and the holy light in Suomucheng’s dream, which inspired him to embark on his journey. In the background, the textured snow mountain is Nyenpo Yurtse Snow Mountain, Suomucheng’s home and where his first pilgrimage began. As Suo said, “Nature is both the biggest obstacle and the most intimate company to pilgrims.” While the transient body movement in the painting contrasts with the heaviness of mountains, the figures also blend into the landscape, as if wanting to become part of it.

I first encountered the ritual of kowtow when I was fifteen, traveling in Qinghai with my parents in midsummer. Among the bustling crowd and unceasing noises of Ta’er Temple, one figure caught my eyes. Dressed in a red cassock, he stood alone in the corridor in front of the temple. Suddenly his whole body fell to the ground. His hands stretched from his chest over to his head, with rags in his hands wiping the ground from back to front. He stood up, and fell again, moving forward with the same action, slowly yet tirelessly. His movement was so powerful that I could almost hear the wind blowing with his body. The ground beneath him was wiped so hard and so many times that it shined brightly. “He is a Buddhist who lives in the monastery and practices kowtow every morning till dawn,” the tour guide told us. “There are many like him here.” Many tourists stopped to watch this scene, yet the Buddhist performed meticulously as if no one was around him. Sweat glistened on his forehead like crystalized beads. At that moment, I felt like I was stepping into a force so tenacious and unbreakable that nothing in this world could stop the Buddhist from performing his ritual. Around him time seemed to fade away. All the trifling disturbances of life were reduced and erased by the repetition of one simple body movement.

Six years later, I had the chance to interview Suomucheng, a Qinghai-Tibetan Tantric yogi and disciple of Qinghai Longshijia Dharma King. Suomucheng has had two pilgrimage experiences: one in 1988, from Mentang in Qinghai province to Guanyin Bridge in Sichuan province, and one in 1999, from Guanyin Bridge to Lhasa. In the interview that follows, Suo shares his motivations and reflections on pilgrimages. His experience was unique, yet it is only one of the thousands of stories about Buddhist pilgrimage and Long Kowtow. People of different ages, genders, backgrounds, and identities begin their journeys for different reasons and at different times. During the pilgrimages, some have died, some were born. People prostrate more than 2,000 kilometers with their head kowtowed, eat the simplest food, sleep on the road, give and receive kindness along the way, and simply keep going and praying without anger, complaints, or distractions. To me, this ritual deeply connects with nature and transcends what we normally consider to be a happy, material life.

Elina Chen: What is the significance of Long Kowtow in Tibetan Buddhism?

Suomucheng: The Long Kowtow is a fusion of Buddhism and Han culture in Tibet. It originates from kowtow in Chinese Han culture—the custom of salute and deep respect when you meet someone. Under the context of Buddhism, the etiquette of kneeling evolves into Long Kowtow—the ritual of five-body prostration with prayers—to express piety of our beliefs. It is a way of praying for the blessings of Buddha, a mentality to avoid disasters, and also a respect for all the masters, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas.

EC: It is such a pleasure to meet you, Suomucheng. Tell us about your two pilgrimage experiences. What was your motivation to go on the pilgrimage? How long did each of them take?

SMC: When I was thirty-five, I saw a red light flickering in the east, like Dharma’s holy light was calling to me. That night, I dreamed of kowtowing all the way to the east—and came up with the thought of prostration to the east until I met Jiarong Mahasiddha.1 In 1988, at the age of thirty-six, I officially set off to my first pilgrimage, kowtowing from my hometown Mentang to Guanyin Bridge. To Buddhists, if we don’t use this life to clear karma we created in the past, even if we gain a human body in the next life, it will be difficult to encounter the Dharma, let alone study, think, and cultivate our practice. Even though we had little money when we began the pilgrimage, everything we needed was in kowtow. Kowtow is a way to gain enlightenment and clear karma.

I was accompanied by two men from the same village. We carried tents, food, and clothes together. We went through all the ups and downs along the way. The lifestyle was simple. We woke up early in the morning, had three meals a day, and prostrated until the night fell.

I always wanted to go to Lhasa. On December 13, 1998, I began the pilgrimage to Lhasa with my eighteen-year-old niece. We took the car from Mentang to Guanyin Bridge. I isolated myself in a retreat cave on Guanyin Bridge for more than two months. One day in the cave, all kinds of colorful mantras appeared on the surface of the cave. My niece and I both saw them with our own eyes. From that day onwards, February 19, 1999, we began kowtowing to Lhasa. It took us almost half a year to get to our destination.

EC: What did you take on your pilgrimage? What clothes did you wear? What did you eat? How did you sleep?

Elina Chen: What is the significance of Long Kowtow in Tibetan Buddhism?

Suomucheng: The Long Kowtow is a fusion of Buddhism and Han culture in Tibet. It originates from kowtow in Chinese Han culture—the custom of salute and deep respect when you meet someone. Under the context of Buddhism, the etiquette of kneeling evolves into Long Kowtow—the ritual of five-body prostration with prayers—to express piety of our beliefs. It is a way of praying for the blessings of Buddha, a mentality to avoid disasters, and also a respect for all the masters, Buddhas, and Bodhisattvas.

EC: It is such a pleasure to meet you, Suomucheng. Tell us about your two pilgrimage experiences. What was your motivation to go on the pilgrimage? How long did each of them take?

SMC: When I was thirty-five, I saw a red light flickering in the east, like Dharma’s holy light was calling to me. That night, I dreamed of kowtowing all the way to the east—and came up with the thought of prostration to the east until I met Jiarong Mahasiddha.1 In 1988, at the age of thirty-six, I officially set off to my first pilgrimage, kowtowing from my hometown Mentang to Guanyin Bridge. To Buddhists, if we don’t use this life to clear karma we created in the past, even if we gain a human body in the next life, it will be difficult to encounter the Dharma, let alone study, think, and cultivate our practice. Even though we had little money when we began the pilgrimage, everything we needed was in kowtow. Kowtow is a way to gain enlightenment and clear karma.

I was accompanied by two men from the same village. We carried tents, food, and clothes together. We went through all the ups and downs along the way. The lifestyle was simple. We woke up early in the morning, had three meals a day, and prostrated until the night fell.

I always wanted to go to Lhasa. On December 13, 1998, I began the pilgrimage to Lhasa with my eighteen-year-old niece. We took the car from Mentang to Guanyin Bridge. I isolated myself in a retreat cave on Guanyin Bridge for more than two months. One day in the cave, all kinds of colorful mantras appeared on the surface of the cave. My niece and I both saw them with our own eyes. From that day onwards, February 19, 1999, we began kowtowing to Lhasa. It took us almost half a year to get to our destination.

EC: What did you take on your pilgrimage? What clothes did you wear? What did you eat? How did you sleep?

SMC: We bought tools for Long Kowtow. We wore monk cassocks. We ate tsampa,2 ghee, and homemade snacks. We lived in tents. On our way from Guanyin Bridge to Lhasa, I bought a donkey that carried food and tents for me and my niece. I named the donkey Ang’er.

EC: Throughout your two pilgrimages, what was the most unforgettable memory and what was the biggest obstacle?

SMC: One of the things that impressed me the most during the pilgrimage were the people we met. The herdsmen were extremely kind in their hearts. They gave us food, water, and medicines when we were in need. Before going on the pilgrimage, I heard stories of encountering robbers and wild animals. We didn’t go through any of those dangers. For me, the only obstacle was the weather. The weather was always capricious. There were hot times and cold times. When it was cold, my body froze. Hands, upper body, and knees could get hurt easily. My friend Zong who went on the first pilgrimage with me got frostbite on his hand. Luckily, he took some local medicine and quickly recovered. When it was hot, my body sweated a lot. My mind became sleepy, and it became difficult to move. But coldness and heat are interconnected, just like obstacles and joy. To get rid of the pain, I practiced prayers over and over again. Through pain I gained joy, and felt closer to Dharma. The strength and spirit of my friends, Sangdancuomu (my niece), and Ang’er (the donkey) also supported me to kowtow to the holy land.

Nature was our intimate counterpart. On one hand, it posed difficulties like the unpredictable weather. On the other hand, it gave me so much joy and eased my mind. No matter where I was on pilgrimage, the sky was always there and would never change. When I stood and listened carefully, I could hear wind blowing across the branches, voices of animals from near and distant mountains, and sometimes love songs of local Tibetans. These sounds, so pure and beautiful, touched my inner kindness and compassion. They made my inner self heard and set up my mind to clear my past karma. When I lay on the ground, the vastness and earthly smell of mountains calmed and placated me. I stood up. I laid down. No matter how I repeatedly moved my body, the sky and the mountain stayed the same. I felt like my body was so light, so ephemeral, and the earth so heavy, and so immortal. My body almost wanted to become part of the earth. These feelings must be a gift from the sacred nature.

EC: Throughout your two pilgrimages, what was the most unforgettable memory and what was the biggest obstacle?

SMC: One of the things that impressed me the most during the pilgrimage were the people we met. The herdsmen were extremely kind in their hearts. They gave us food, water, and medicines when we were in need. Before going on the pilgrimage, I heard stories of encountering robbers and wild animals. We didn’t go through any of those dangers. For me, the only obstacle was the weather. The weather was always capricious. There were hot times and cold times. When it was cold, my body froze. Hands, upper body, and knees could get hurt easily. My friend Zong who went on the first pilgrimage with me got frostbite on his hand. Luckily, he took some local medicine and quickly recovered. When it was hot, my body sweated a lot. My mind became sleepy, and it became difficult to move. But coldness and heat are interconnected, just like obstacles and joy. To get rid of the pain, I practiced prayers over and over again. Through pain I gained joy, and felt closer to Dharma. The strength and spirit of my friends, Sangdancuomu (my niece), and Ang’er (the donkey) also supported me to kowtow to the holy land.

Nature was our intimate counterpart. On one hand, it posed difficulties like the unpredictable weather. On the other hand, it gave me so much joy and eased my mind. No matter where I was on pilgrimage, the sky was always there and would never change. When I stood and listened carefully, I could hear wind blowing across the branches, voices of animals from near and distant mountains, and sometimes love songs of local Tibetans. These sounds, so pure and beautiful, touched my inner kindness and compassion. They made my inner self heard and set up my mind to clear my past karma. When I lay on the ground, the vastness and earthly smell of mountains calmed and placated me. I stood up. I laid down. No matter how I repeatedly moved my body, the sky and the mountain stayed the same. I felt like my body was so light, so ephemeral, and the earth so heavy, and so immortal. My body almost wanted to become part of the earth. These feelings must be a gift from the sacred nature.

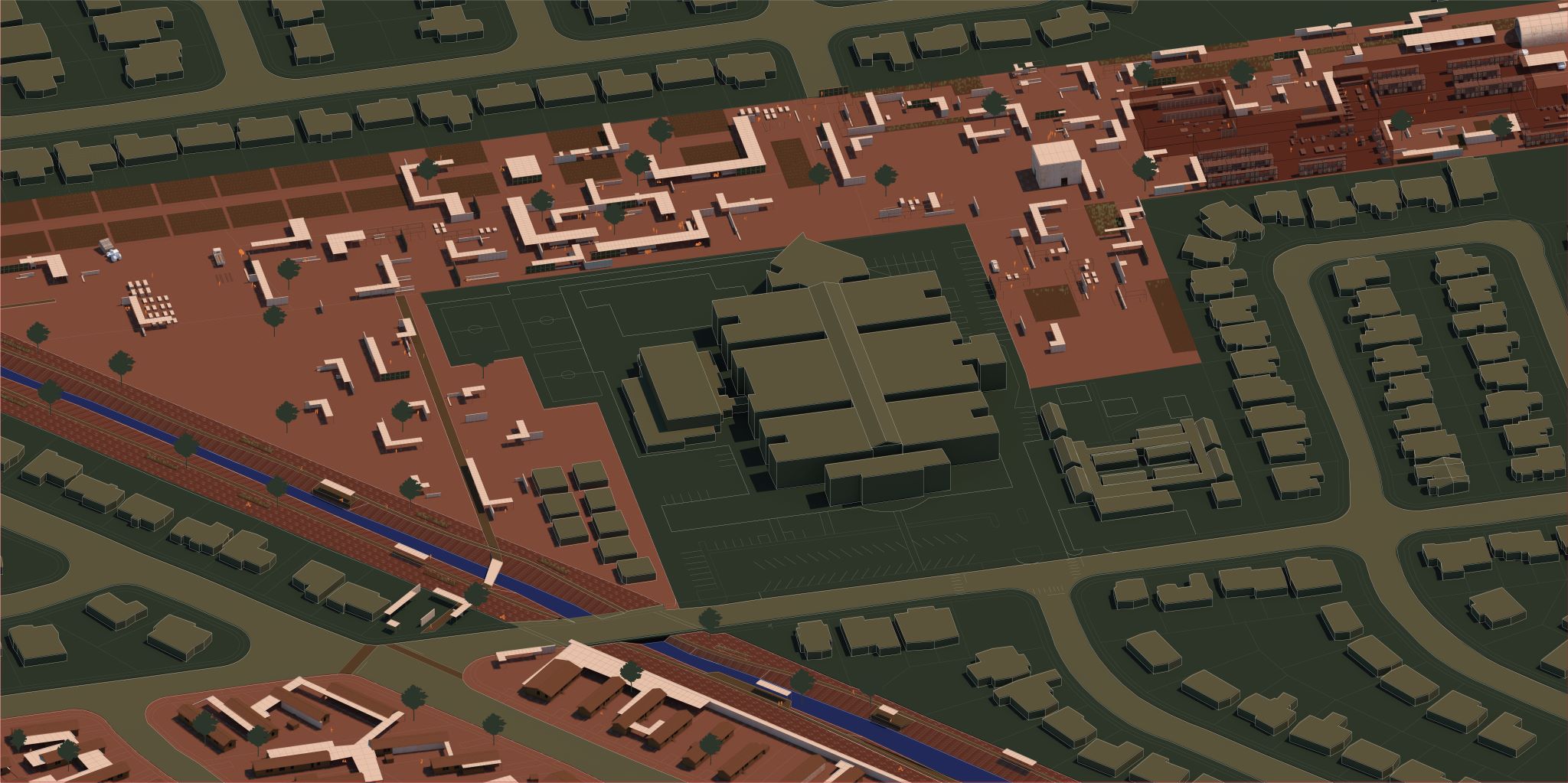

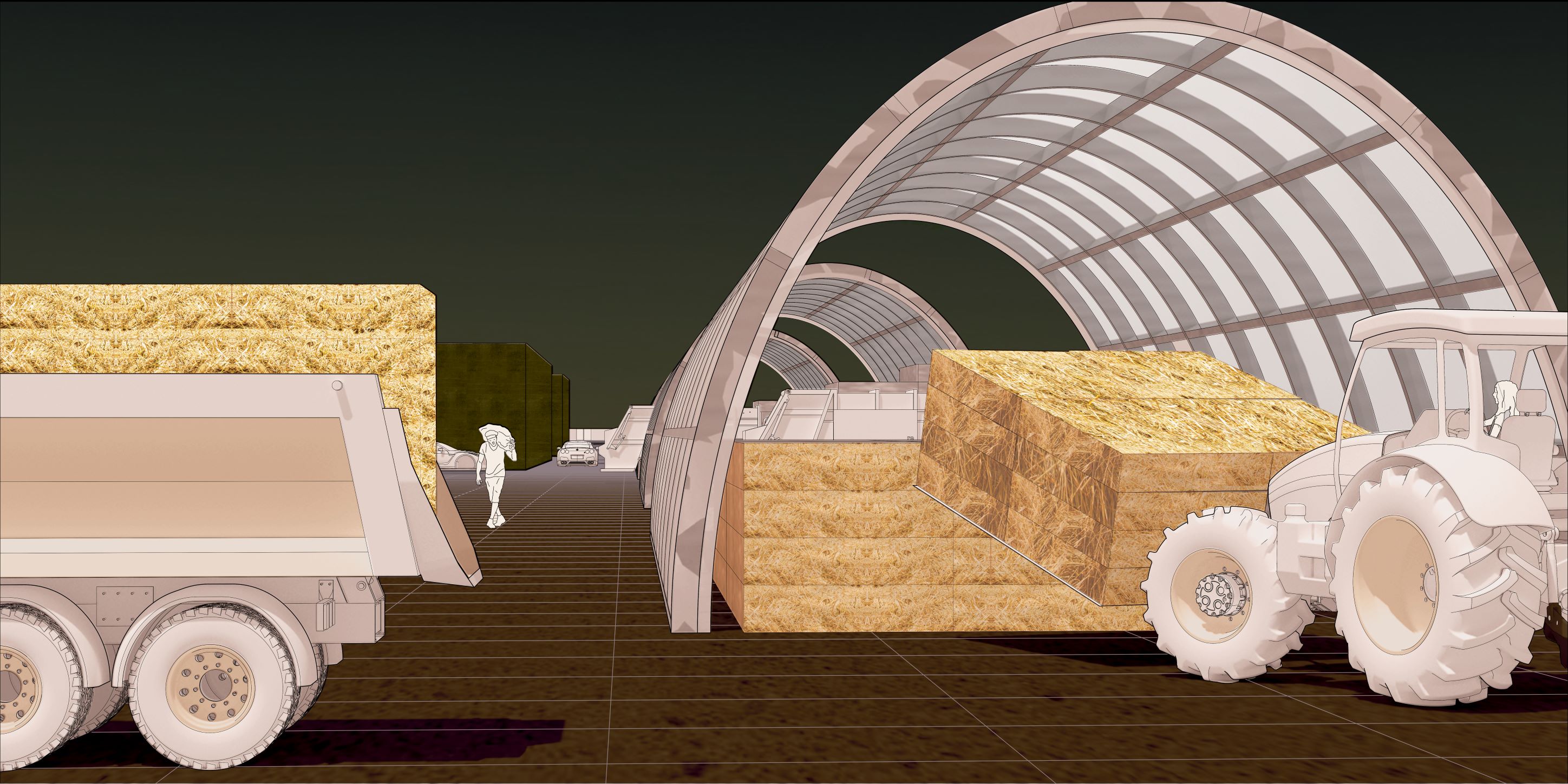

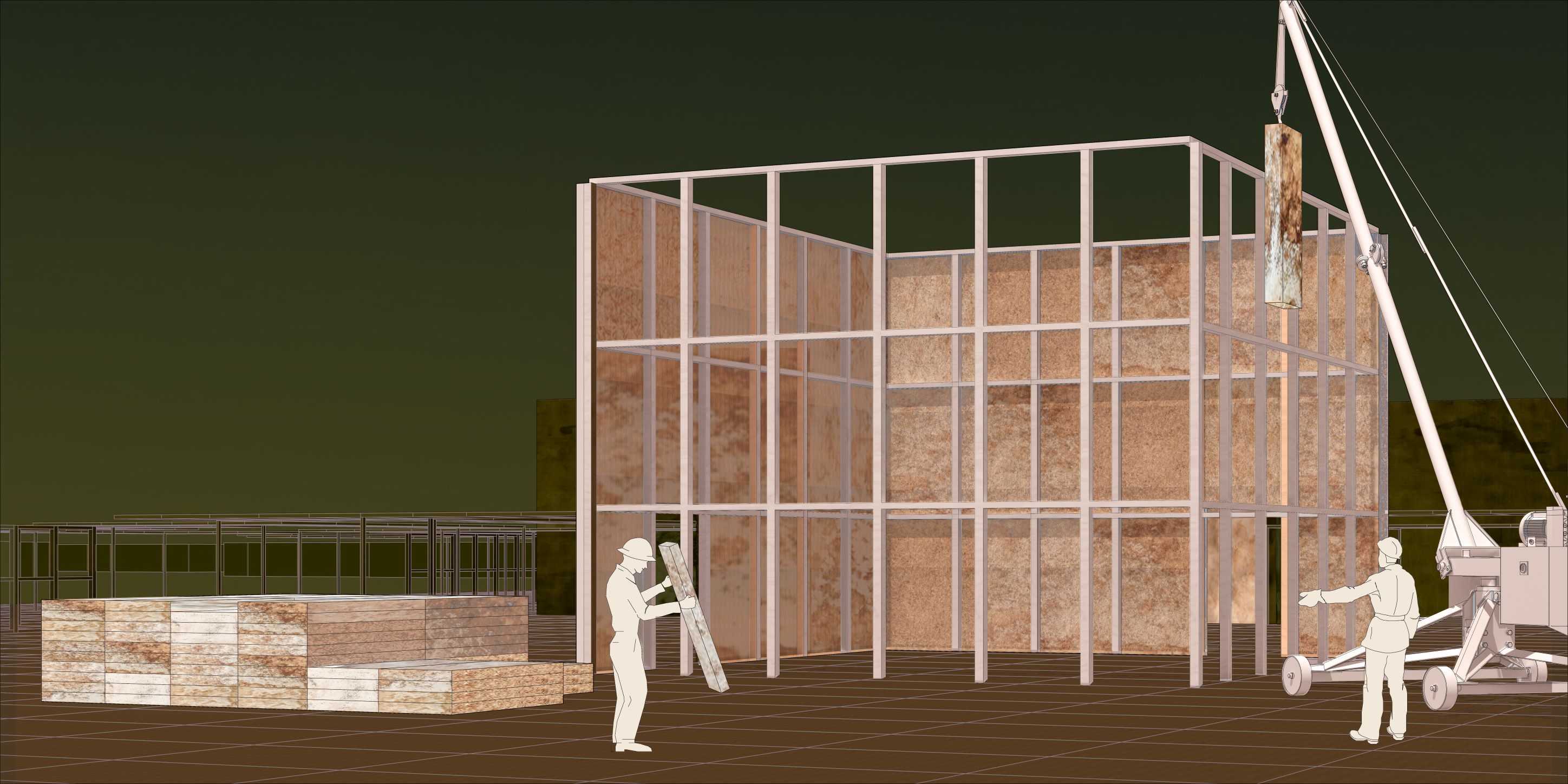

Mycelium as Connective Building Tissue

Mycelium is a network of fungal roots that can function as non-formaldehyde adhesive glue in binding organic wastes into constructing materials such as particle boards. Through introducing mycelium panels as connective building tissue, we design a carbon neutral, circular manufacturing and building system.Instead of a linear process going from extraction to production, consumption, and waste, we propose a circular system where agricultural waste distribution, mycelium cultivation, structure construction, and material decay can all take place within the selected site.

Connectivity, the thesis of our design proposal, takes place on three levels: first, on the territorial level, informed by the life cycle of mycelium material,we introduce an urban strategy that connects the river valley context of El Paso-Ciudad Juárez with agricultural waste sourcing, lab manufacturing, mobile housing improvement and waste reuse. Second, on the urban level, we design a manufacturing and exhibiting site that mass produces standardized mycelium panels and connects with the surrounding neighborhoods through mycelium experimental structures, an urban garden, and a farmers’ market. Third, on the architectural level, we use mycelium panels to infiltrate mobile housing neighborhoods, providing insulation and new circulation that connects isolated housings into communal spaces.

Left images: (1) Stage I: substrates are transported into the storage and prepared for mass production of mycelium panels. (2) Stage II: an experimental structure is built to exhibit the architectural qualities of mycelium panels. In the third stage, an urban garden is built with mycelium panels, using the design strategy that we showed in the concept collage. (3) Stage III: mycelium panels start to infiltrate mobile housing neighborhoods. Standardized panels start to create conditions such as courtyards, backyards, alleyways for different activities such as barbecues and collective cooking, shading parking shelters, and acoustic walls to block traffic noise. At the same time, build-at-home kits, which include packaged substrates, moulds, and a self-built instruction manual, will enable individuals to cultivate and produce mycelium panels to replace degraded ones, using their own kitchen space.

Fall 2021, collab with Tony Dai.

Mycelium is a network of fungal roots that can function as non-formaldehyde adhesive glue in binding organic wastes into constructing materials such as particle boards. Through introducing mycelium panels as connective building tissue, we design a carbon neutral, circular manufacturing and building system.Instead of a linear process going from extraction to production, consumption, and waste, we propose a circular system where agricultural waste distribution, mycelium cultivation, structure construction, and material decay can all take place within the selected site.

Connectivity, the thesis of our design proposal, takes place on three levels: first, on the territorial level, informed by the life cycle of mycelium material,we introduce an urban strategy that connects the river valley context of El Paso-Ciudad Juárez with agricultural waste sourcing, lab manufacturing, mobile housing improvement and waste reuse. Second, on the urban level, we design a manufacturing and exhibiting site that mass produces standardized mycelium panels and connects with the surrounding neighborhoods through mycelium experimental structures, an urban garden, and a farmers’ market. Third, on the architectural level, we use mycelium panels to infiltrate mobile housing neighborhoods, providing insulation and new circulation that connects isolated housings into communal spaces.

Left images: (1) Stage I: substrates are transported into the storage and prepared for mass production of mycelium panels. (2) Stage II: an experimental structure is built to exhibit the architectural qualities of mycelium panels. In the third stage, an urban garden is built with mycelium panels, using the design strategy that we showed in the concept collage. (3) Stage III: mycelium panels start to infiltrate mobile housing neighborhoods. Standardized panels start to create conditions such as courtyards, backyards, alleyways for different activities such as barbecues and collective cooking, shading parking shelters, and acoustic walls to block traffic noise. At the same time, build-at-home kits, which include packaged substrates, moulds, and a self-built instruction manual, will enable individuals to cultivate and produce mycelium panels to replace degraded ones, using their own kitchen space.

Fall 2021, collab with Tony Dai.